IPR@50: The Third Decade (1989–1998)

Identity and Ambitions

Get all our news

IPR researchers continued the study of persistent poverty in America.

This is the third of a five-part series that will examine how IPR has grown and evolved in each decade. IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach offers a preview of the June 6-7 anniversary conference here.

[View a timeline of IPR's Third Decade]

CUAPR to IPR

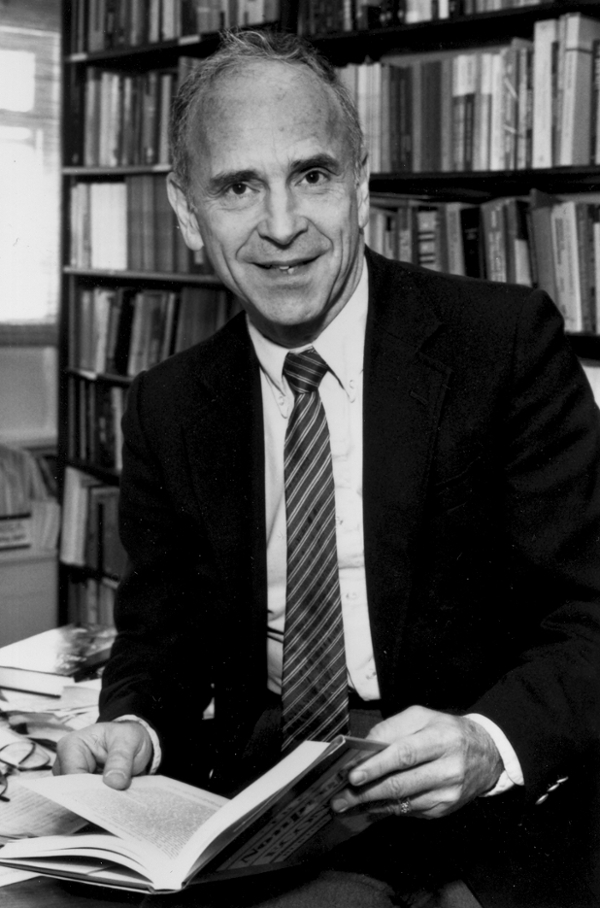

In 1990, Northwestern recruited economist Burton Weisbrod from the University of Wisconsin-Madison to become the fourth director of the Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research (CUAPR).

Weisbrod first became acquainted with the Center as an outside faculty evaluator of its work shortly before its third director Margaret Gordon left to become Dean of the Evans School at the University of Washington. The Center “intrigued” him in several ways when he was approached about the directorship.

director in 1990.

He was impressed that the university had continued to support CUAPR. “And the idea of trying out administration was something that appealed to me,” he said.

Under Weisbrod’s leadership, the Center acted to address current policy events as part of his vision of creating a premier national social policy center. Conferences and research projects examined, among others, the Clinton administration’s 1993 healthcare reform proposals, implementation of famed Yale child psychiatrist James Comer’s ideas for school development, decentralization of the Chicago Public Schools, connections between the media and the Los Angeles riots following the 1991 police beating of Rodney King, and fallout from Operation Greylord, a large corruption investigation into the Cook County judiciary.

Social policy professor Fay Lomax Cook inherited this strong research and outreach program from Weisbrod when she took over as acting director in 1995. One of her first acts was to explore a name change with the Center’s executive committee and the University’s administration.

“People didn't understand what the Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research really was,” she explained. “We also felt that it didn't encapsulate everything that faculty had been doing; it was too narrow. It was about urban affairs, but the name needed to signal that we also addressed state and national issues.”

As Cook took up her new position in September 1996, it was as director of the Institute for Policy Research. Not only did the new name indicate a more comprehensive focus—policy research over urban affairs—but it also reflected an upgrade in organizational status in moving from a center to an institute. This name change would set the stage for larger social policy research projects with a national focus.

The Joint Center for Poverty Research

One of the largest projects to occur during this decade grew out of an ongoing IPR focus, the study of poverty and social welfare policy.

Beginning in 1990, IPR ran a joint PhD-level interdisciplinary training program in urban poverty with the University of Chicago, supported by the National Science Foundation. Then in 1996, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services awarded the two institutions a $7.5 million, five-year contract for a new national poverty center—the Joint Center for Poverty Research (JCPR)—to foster research, student training, and other scholarly activities related to persistent poverty.

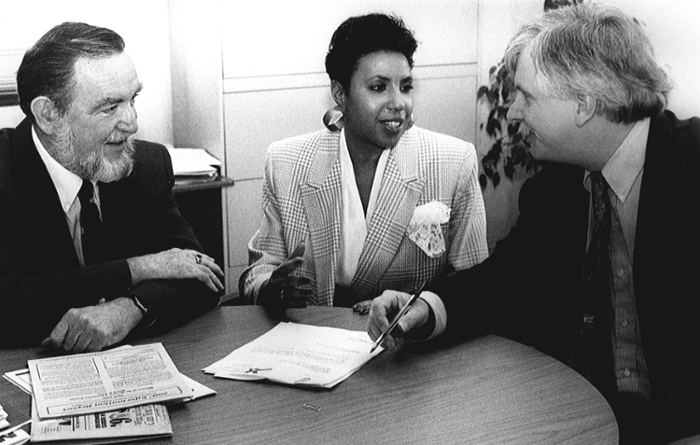

discusses school reforms with Fay Lomax Cook.

Landing the new venture required significant effort, Cook remembered, and was not assured.

“There were many naysayers who said we shouldn't have tried,” Cook said, noting that the University of Wisconsin had run a national poverty center for many years.

“I think what was really crucial is that we made the decision that we would be stronger together with the University of Chicago. And that was a major change,” she said.

A significant number of IPR faculty who studied poverty and social welfare became JCPR faculty affiliates. JCPR leadership shifted every two years between the two institutions. Its first director was Rebecca Blank, an IPR economist who later served in the Clinton and Obama administrations and is now chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“We really made the intellectual and psychological distance between the two universities seem much shorter than it had ever been. And I think that that was part of the key to our success,” Cook said.

From 1998–2000, Greg Duncan, an economist and nationally renowned poverty researcher, served as JCPR’s deputy director, while Susan Mayer of the University of Chicago Harris School, who received her PhD in sociology from Northwestern and was a former IPR graduate assistant, was its director. In 2001, Duncan became director.

JCPR promoted scholarly investigation into poverty by creating a national network of senior poverty researchers, making small grants to junior scholars, and establishing a graduate fellows program for PhD students in multiple disciplines. Research seminars rotated between Evanston and Chicago, and JCPR published a quarterly newsletter and a working paper series.

IPR scholars affiliated with JCPR explored social welfare policy, a changing labor market, income and wages, the school-to-work transition, and housing policy, among other topics. Consequences of Growing Up Poor (1997), co-edited by Duncan, examined how economic deprivation put children at risk. Economist and IPR associate director Joseph Altonji investigated the white/black gap in wealth, finding that a key cause of the gap was in the relationship between income and wealth. Sociologist Mary Pattillo researched the socioeconomic fragility of the black middle class; her findings appeared in her 1999 book, Black Picket Fences.

Building Communities

Community development was also a long-term IPR concentration. The community studies program at IPR, under John McKnight’s direction from its earliest days, looked for internal resources within urban neighborhoods rather than focusing exclusively on data that defined low-income neighborhoods by their deficits and failures.

To reach as many communities as possible, McKnight and long-time research associate John Kretzmann wrote Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets, published by CUAPR in 1993. This guide to “asset-based community development” suggests how communities can mobilize the capacities of their various constituents and has sold more than 100,000 copies over the years.

John McKnight, Romelle Moore-Robinson, and

John Kretzmann discuss IPR's community

development work.

In 1995, McKnight and Kretzmann created the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute, housed at IPR, to redirect communities from the traditional “needs and deficiencies” model of development to more effective methods of community building using assets found within their neighborhoods.

The 1990s were a fertile period of research at IPR, only briefly touched on here. One of IPR’s key strengths is evident in these years—providing a space for the engagement and exchange of scholars committed to understanding the world around them and to developing policies to improve how people live.

And, as Fay Cook points out, judicious funding also played a key role. “I think part of the success of IPR has been the ability to recognize new ideas and great ideas and then just put a little seed money into the ideas and give our scholars a chance to make them grow,” she said.

Burton Weisbrod is Cardiss Collins Professor of Economics and was IPR director from 1990–95. He joined IPR from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he directed the Center for Health Economics and Law. He has also served on the Council of Economic Advisors to presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson and on the National Advisory Research Resources Council of the National Institute for Health. Fay Lomax Cook is professor of human development and social policy and served as director from 1996–2012. From 2014–18 she was assistant director of the National Science Foundation (NSF) heading its Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences Directorate.

Find out more about the IPR@50 Conference here.

Article by Evelyn Asch, IPR Research Associate. Photo credits: Top: iStock; IPR Archives: Weisbrod, Comer and Cook, McKnight, Moore-Robinson, and Kretzmann.

Read the previous articles in the IPR@50 series: Innovation and Continuity: The First Decade (1968–1978) and Neighborhoods and New Methods: The Second Decade (1979-1988).

Published: May 13, 2019.