IPR@50: The Second Decade, 1979–1988

Neighborhoods and New Methods

Get all our news

Stateway Gardens, one of the Chicago Housing Authority’s high-rise public housing complexes, housed nearly 7,000 people in 1973. In 1976, the landmark public housing discrimination case, Hills v. Gautreaux, changed public housing in Chicago.

This is the second of a five-part series that will examine how IPR has grown and evolved in each decade. IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach offers a preview of the June 6-7 anniversary conference here.

[View a timeline of IPR's Second Decade]

What would moving to new communities mean to people living in segregated public housing? How do crime and the fear of crime change people’s behavior? Would hosting a world’s fair help or hurt Chicago? The researchers at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) tackled these questions and more in the 1980s.

IPR—then still called the Center for Urban Affairs—entered its second decade as a well-established and respected research hub of the University. The Center’s faculty, researchers, and students focused for the most part on Chicago and other cities for their data, working with community organizations, city officials, and ordinary citizens while employing the most modern methods of the day.

James Rosenbaum, IPR education researcher, joined IPR in 1979 and remembered that “we, the people who asked questions” were “looking at real world happenings.” Engaging with people and their concerns about housing, crime, or traffic in their neighborhoods was a way to use concrete details to understand large issues.

A New Director and a New Name

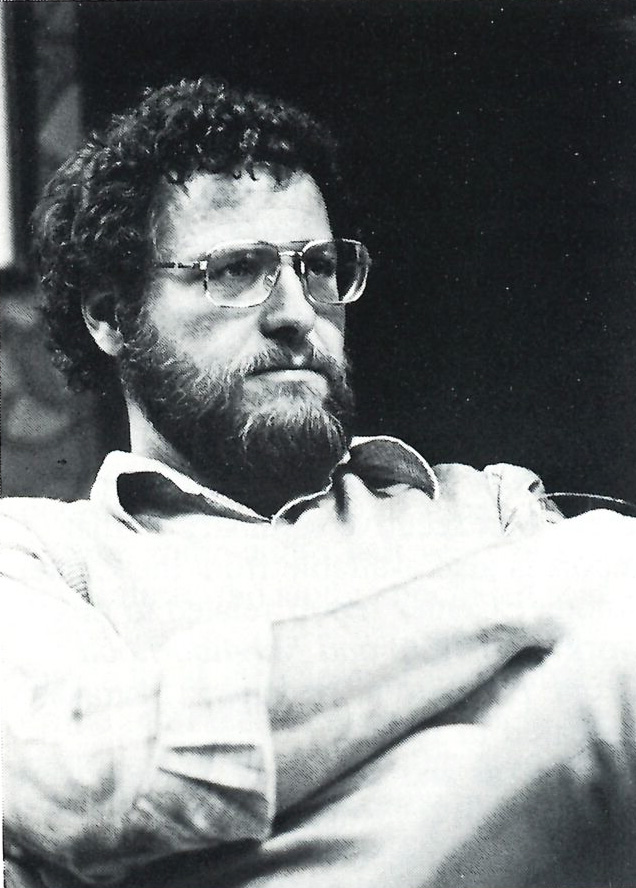

director in 1980.

After nine years as the director, Louis Masotti stepped down as director in August 1980, and Margaret Gordon became IPR's third director. A Northwestern PhD, she came to the Center as a research associate in 1972 and joined the Center faculty in 1974 with a joint appointment in journalism and sociology. She served as director for 10 years.

In fall 1980, the executive committee voted unanimously to become the Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research to reflect the realities of a changing research agenda.

Funding sources were changing as well. As Gordon noted in 1986, under the Reagan Administration, “there have been decreasing amounts of money available through federal agencies,” but foundation dollars were making up for much of that loss.

Major Research

Several signature research projects highlight IPR’s second decade, notably the Reactions to Crime studies and the Residential Mobility projects, which studied the impact of the landmark Chicago public housing discrimination case, Hills v. Gautreaux, decided in 1976.

IPR faculty emeritus Wesley G. Skogan and Dan Lewis, social policy professor and IPR associate, were among the early participants in the Reactions to Crime research that began in the mid-1970s and continued well into the 1980s.

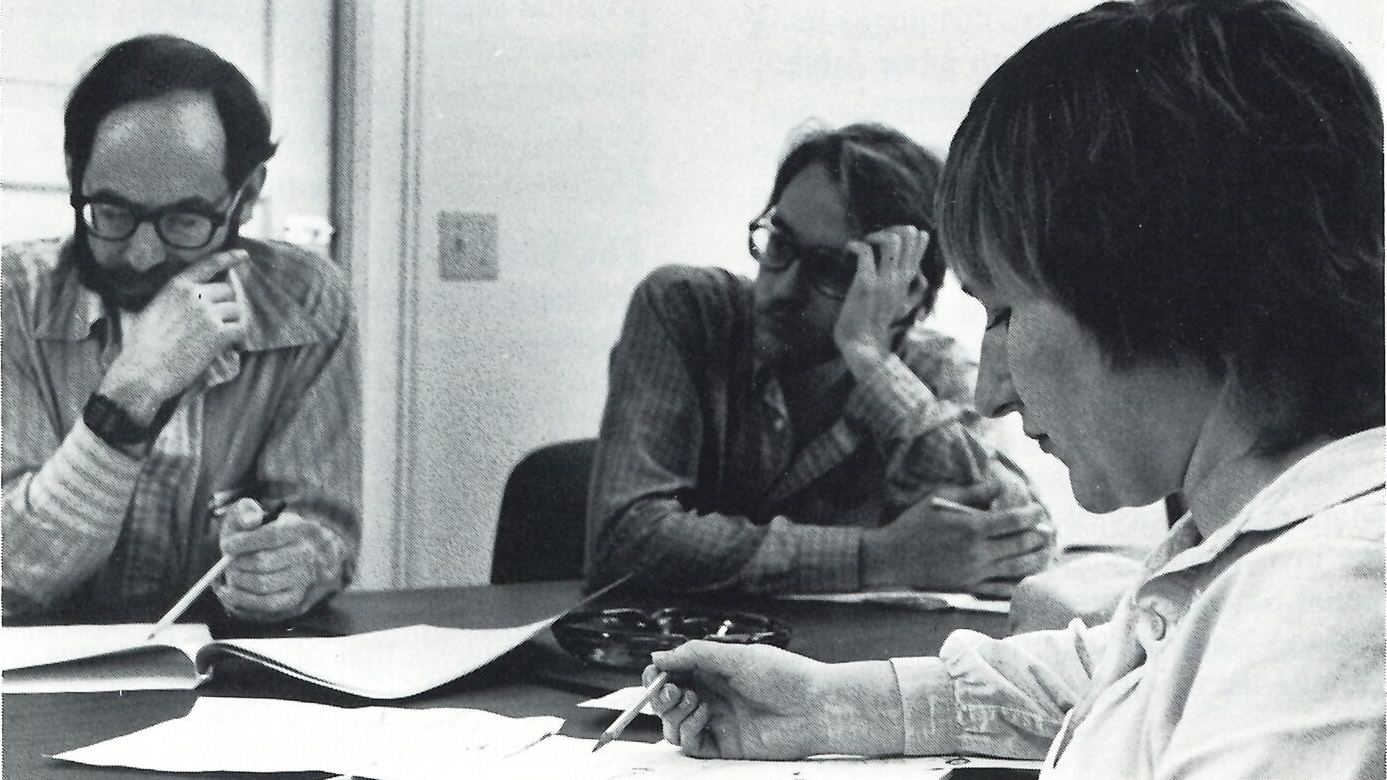

on the Center's crime studies.

A cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Justice, which was not a grant but negotiated federal funding, enabled the project to investigate “not just fear, but what we call reactions to crime,” Skogan said. The project involved field work by ethnographic observers, interviewers, field workers, and surveys and analyses of aggregate data in Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, he said. The research produced important findings that have influenced our thinking about how people respond to crime.

Rosenbaum fortuitously came to work on the housing and education issues raised by the Gautreaux program because he was Center faculty.

“IPR was crucial here. It would not have happened if Margo [Gordon] hadn’t had discussions with Alexander Polikoff [the attorney who argued the Gautreaux case]," he recalled. “She wrote a memo to everybody who would be interested in studying this. And I said, 'I’m too busy now, but it looks like something somebody ought to do,' and then I decided I better do it. There was no one else to do it.”

From 1981–1985, Rosenbaum, along with other Center faculty including law professor and IPR associate Leonard Rubinowitz and Dan Lewis, followed low-income inner-city black children who attended predominantly white schools in the Chicago suburbs after their families relocated under the Gautreaux decision.

The study “showed remarkable results,” Rosenbaum said. “I mean, earth-shattering momentous changes in people's life situations and in their lives. … Kids moved from bad neighborhoods where they had to sleep in the bathtub to avoid gunfire to peaceful suburbs with good schools, and they discovered they were pretty good in school—some of them were very good.”

Working with Citizens and Government with New Methods

In methodology and outreach, Center faculty were in the vanguard of social science research.

The Reactions to Crime and other projects relied on survey techniques that Center faculty helped refine. The Center founded the Northwestern Survey Laboratory in 1983, directed by then-journalism professor Paul Lavrakas, a core member of the crime research team. Into the 1990s, the lab, headquartered in IPR’s 625 Haven Street building, conducted random-digit dialing telephone surveys, serving the Center and other faculty across the University.

Skogan and Rosenbaum remembered how then-sociologist Andrew Gordon would lug one of the earliest personal computers—a Macintosh—with him to meet with neighborhood groups. The computer “was a big thing and Andy was big enough that he could carry it easily,” Rosenbaum said. “But the rest of us struggled with it a little bit.”

Gordon studied how neighborhoods could use these new portable computers to analyze their community problems, such as where there were dangerous intersections or robberies.

with Center colleagues.

Engagement and cooperation with local government was a distinguishing characteristic of the Center during its second decade. Rosenbaum noted that when he arrived, he was very impressed by “the degree of connections and even trust between some offices in city government, some administrative services in different fields, and Northwestern.”

During the first half of 1979, Masotti served as the head of Chicago Mayor Jane Byrne’s transition team. Other faculty members served Harold Washington during his years as mayor.

Long-time faculty member economist Marcus Alexis chaired the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on the proposed 1992 Chicago World’s Fair. In 1984, the Center sponsored a series of eight public forums to explore the possible impacts of a World’s Fair. Distinguished panels discussed issues such as what a fair might mean to neighborhoods, economic development, and culture. As Skogan recalled, among faculty there was “skepticism whether the best investment of the city’s resources was in a world’s fair.”

The 1992 Chicago World’s Fair never happened. But IPR’s engagement in questions facing cities and in making rational policy choices continued.

IPR faculty made the most of their access to urban problems in the 1980s. “It was a particularly good time to be focused on local issues because that’s where the innovative activity was happening,” Rosenbaum said.

Wesley G. Skogan is an emeritus IPR fellow and professor of political science who joined IPR in 1974. James Rosenbaum is an IPR fellow and professor of education and social policy, and sociology. He joined IPR in 1979.

Find out more about the IPR@50 Conference here.

Article by Evelyn Asch, IPR Research Associate. Photo credits: John White, National Archives (top), IPR/NU Archives (Margaret Gordon, Wesley Skogan, and James Rosenbaum, Galen Carey, and Cheryl Coppell).

Read the first article in the IPR@50 series: Innovation and Continuity: The First Decade (1968–1978).

Published: April 10, 2019.