‘Turning the Ship’ of Climate Change

Former Energy Secretary charts a path to net-zero emissions during a packed lecture at Northwestern

Get all our news

It takes three quarters of a century to turn the ship. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try as hard as we can now. ”

Steven Chu

William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Physics and Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University

Watch the video:

Nobel Prize-winning physicist and former U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu shares insights on possible ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

By 2050, over 215 million people—more than the population of Brazil—will be displaced from their homes and communities because of climate change, according to the World Bank.

For Steven Chu, Nobel Prize-winning physicist and former U.S. Secretary of Energy, these “climate refugee” predictions issue a stark warning: Without immediate, coordinated action, the world is headed toward a climate disaster.

Speaking on April 2 to more than 450 students, faculty, and community members at Northwestern University, Chu drew on his experience as both a scientist and former Cabinet member to outline the urgent steps needed to achieve net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions and avoid some of climate change’s major consequences.

Northwestern’s Vice President for Research Eric Perreault noted his achievements in both science and policy.

“The breadth of your work, from physics to biology to government, is really incredible, and it makes you a perfect choice for today's lecture at Northwestern,” Perreault said. “This is an opportunity to talk about a challenge that is truly interdisciplinary.”

Chu’s visit marked the first Distinguished Public Policy Lecture jointly hosted by the Institute for Policy Research and the Paula M. Trienens Institute for Sustainability and Energy.

IPR Director Andrew Papachristos emphasized the importance of hosting a speaker whose career reflects Northwestern’s commitment to solving problems across disciplines, and whose knowledge can help the Northwestern community make sense of the chaotic current moment.

“We are very lucky to have him here today to talk about how we got to the place where we are, where we find ourselves today, where droughts, flooding, and extreme heat waves fundamentally alter the lives of people around the globe,” Papachristos said.

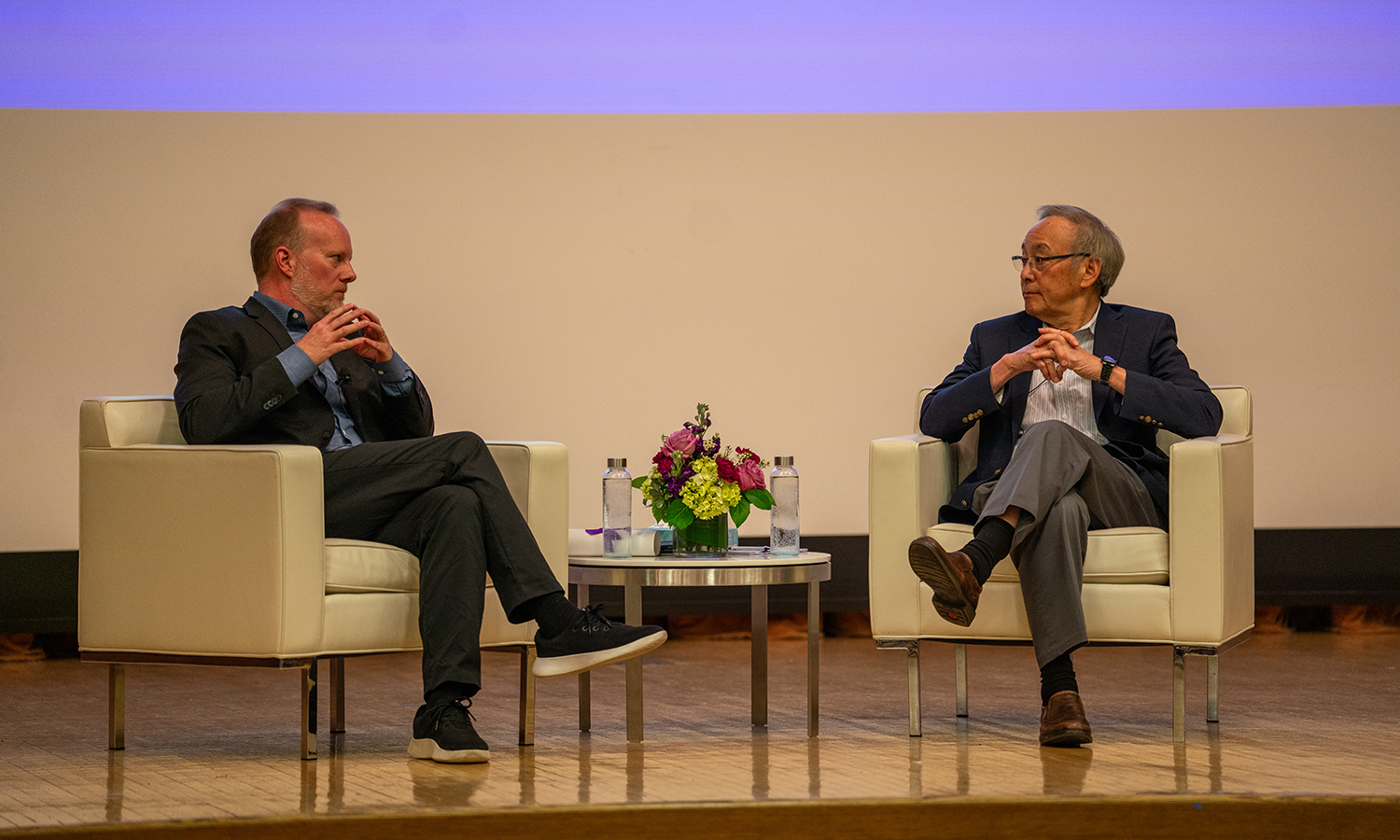

Steven Chu (right) sat down for a conversation after his lecture

with Trienens Institute Executive Director Ted Sargent.

Where We Are

Chu started his wide-ranging lecture with an overview of where we are and where we’re headed. Global temperatures have been rising since 1850, with 2024 confirmed as the warmest year ever recorded. The temperature of global record is bubbling over 1.5 degrees Celsius, which has implications not only for human and natural systems today, but even more so for the future.

The reason why? Oceans are absorbing 90% of the additional heat trapped by greenhouse gasses, making it harder for climate models to provide an accurate picture of how that heat will affect the planet. Even if we stopped emissions today, he said, scientists would still need between 50 and 100 years to document the new equilibrium.

“That’s very, very disturbing,” Chu said, “because people say, ‘What’s happening is not so bad,’ but they're not going to be around in the next 50 or 100 years.”

Adding to the uncertainty are leaders’ weakening commitments to previous pledges and policies, which factor into current predictions.

“In the last three months, especially, there's been a pullback from these pledges,” Chu said. “So, we don't know really what's going to happen.”

Where We're Headed

Current projections, even accounting for policy and pledges already in place, suggest the world is on track for an increase of 3 degrees Celsius by 2100.

To stay below even a 2-degree increase, we would need to eliminate all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. Chu said this includes emissions from the production of steel, concrete, plastic, and chemicals, all forms of transportation, and the food supply chain—which accounts for a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions.

Chu, who emphasized the importance of history in understanding the arc of technological change and revolution, called for a fourth agricultural revolution to dramatically reduce emissions from food production while maintaining yields. The first three agricultural revolutions were transformative. They fed a rapidly growing global population but led to deforestation, soil degradation, and other environmental costs. For the fourth, he underscored the urgency in addressing agriculture’s biggest source of greenhouse emissions, methane from cattle. Methane, which is released when cattle digest food, is over 28 times as powerful as carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere. Emissions from cattle worldwide equal China’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. But changing dietary habits is hard.

A solution? Modifying the cattle’s diets so they produce less methane.

Chu went on to detail a wide variety of technologies currently under development that could help lower emissions, such as nuclear fission, small modular nuclear reactors, synthetic biology, and new methods of carbon capture, among others.

He also stressed the need to make clean energy more practical. He highlighted how energy storage solutions, particularly long-duration storage like batteries, could make intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind more reliable.

Batteries are becoming lighter, cheaper, and more powerful, fueling the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and providing alternatives to oil and gas. While Tesla helped popularize EVs, Chinese EVs are more efficient, offering greater range with shorter charging times and costing far less. But the U.S. has made strides in catching up to China’s lead in battery innovation, he noted.

To succeed in the transition to renewable energy, Chu said we also must reduce “an insatiable appetite” for energy-intensive AI and machine-learning applications. Our aspiration, he said, should be to emulate the more energy efficient human brain. He noted that a four-year-old only requires around 70 watts of energy—35 of which goes directly to the brain—to complete a complex task, like switching from speaking English to Spanish.

'Turning the Ship'

After his lecture, Chu sat down with Ted Sargent, executive director of the Trienens Institute. Sargent began with the question that many in the audience were wondering, “What can we do?”

Chu said that you have to start by using a metric that reflects your values. He suggested that using GDP as a measure of growth, as we do now, encourages consumption because consumption increases GDP. For example, a building is constructed to last for 50, not 500, years.

“This consumption to ‘use once, throw away’ has to fundamentally change,” Chu said.

We need a new definition of wealth, Chu offered, because GDP does not adequately measure what’s important to us like our health, safety, or education. It also doesn’t reflect the realities of shrinking birth rates and the declining number of workers who can contribute to the coffers of aging populations. But such shifts offer opportunities, too, and countries like China are investing in these technologies because they will lead to wealth creation.

As science and technology in China advance, Chu argued that instead of seeking “political protection” through tariffs, the U.S must return to what it did a century ago—focus on innovation.

“The creativity is still there, and we’ve got to harness that,” he said.

He credited immigrants for much of the country’s technological leadership, emphasizing their role in driving innovation. He also stressed that America’s openness and inclusivity are key strengths that should not be eroded.

“We have to take stock of who we are, the great virtues we have in this country, and play on those strengths,” he said.

Despite the challenges ahead on the path to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, Chu is cautiously optimistic. However, “Don’t be fooled into thinking we’ll be carbon neutral by 2050,” he warned.

To illustrate his message, Chu played a clip from Titanic at the end of his lecture, showing the ship struggling to turn away from an iceberg. In this analogy, the most dismal impacts of climate change are the iceberg: We see them coming and can change course, but progress is slow.

“It takes three-quarters of a century to turn the ship,” Chu said. “That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try as hard as we can now.”

The Institute for Policy Research and the Paula M. Trienens Institute for Sustainability and Energy extend their gratitude to the Department of Physics and Astronomy for their support of the event.

Steven Chu is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Physics and Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University. He won the 1997 Nobel Prize in physics and was U.S. Secretary of Energy under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013.

Photo credits: Rob Hart

Published: April 22, 2025.