New Book Traces How Americans Pushed for Debt Forgiveness

Chloe Thurston explores how 19th-century movements inform 21st-century protests

Get all our news

I think that what we've seen in the last few years points to a resurgence of some of the types of political movements that we saw in the 19th century. ”

Chloe Thurston

IPR political scientist

Recent policy addressing student loan debt, including the pausing of payments during the pandemic and President Biden’s overturned executive order canceling some federal student loans, has raised the question: Who is entitled to debt relief from the government?

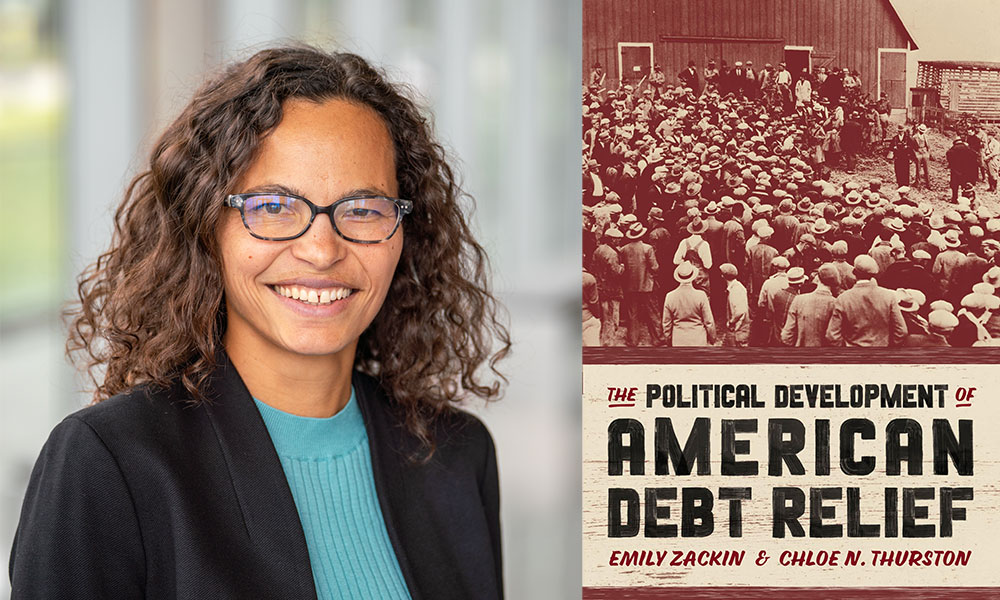

Mobilizing for debt relief has a long history in American politics. In The Political Development of American Debt Relief (University of Chicago Press, 2024), Emily Zackin of Johns Hopkins University and IPR political scientist Chloe Thurston track the rise of debt relief advocacy in the 19th century and its subsequent decline in the 20th century—and its recent resurgence.

Thurston’s interest in debt relief builds on her first book, At the Boundaries of Homeownership: Credit, Discrimination, and the American State (Cambridge University Press, 2018). In the book, Thurston outlines how Black Americans and women were shut out of the housing market and often denied access to credit for a mortgage after WWII. While working on it, she wondered what happened to Americans after they got access to credit.

“I paid a lot of attention to the question of ‘How do you get access to credit?’ but not ‘What happens if you're over-indebted?’” Thurston said about her first book.

In their new book, Zackin and Thurston trace debtor activism across American history. They describe how indebted 19th-century farmers called for government support. Farmers—often perennial debtors—argued that their debt resulted from circumstances outside of their control like bad weather and economic instability.

“They learned over time how to act collectively, and they tended to act collectively through the state legislature,” she said, noting that state governments repeatedly provided debt relief to farmers.

By the 20th century, Americans were largely uninvolved in policy efforts to cancel debt, though more of them were taking it on. Consumer credit rose as Americans borrowed to pay for staples of middle-class life, while a few credit card companies grew to dominate the market and became more organized around policies that would benefit creditors. Stigma about debt also increased. Debt was no longer considered out of one’s control, but the result of poor individual choices.

Like access to credit, U.S. debt relief was racialized and sometimes discriminatory.

“It [debt relief] only really works to the extent that you have assets in the first place to protect,” Thurston said.

She points out how following the Civil War, White landowners in the South economically benefited from government debt relief. Newly freed Black Americans, however, became trapped in a cycle of debt through sharecropping, where landowners rented land to tenants in exchange for a share of their tenants’ crop. In the 1960s, when Civil Rights groups advocated for Black Americans’ access to credit, they were reluctant to draw attention to those who couldn’t repay their loans because their members struggled to get mainstream credit.

By the 21st century, the Great Recession and the pandemic led to a resurgence of debt-related activism through movements like Occupy Wall Street and student loan protests. This time organizations like Black Lives Matter linked debt relief directly to racial justice. Debtors started to see some real policy change—though temporary—during the pandemic in relief from mortgage and student loan payments.

“I think that what we've seen in the last few years points to a resurgence of some of the types of political movements that we saw in the 19th century,” Thurston said.

Though these movements do not match the size or influence of earlier debt relief movements, she says activists are drawing on the playbook of 19th-century protestors. Today, they are using the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic to destigmatize individual debt and argue that their debt is due to broader structural forces.

“That's both new today, but also a return to that earlier language that farmers were using,” Thurston said.

Chloe Thurston is associate professor of political science.

Photo credit: Headshot by Rob Hart

Published: November 25, 2024.