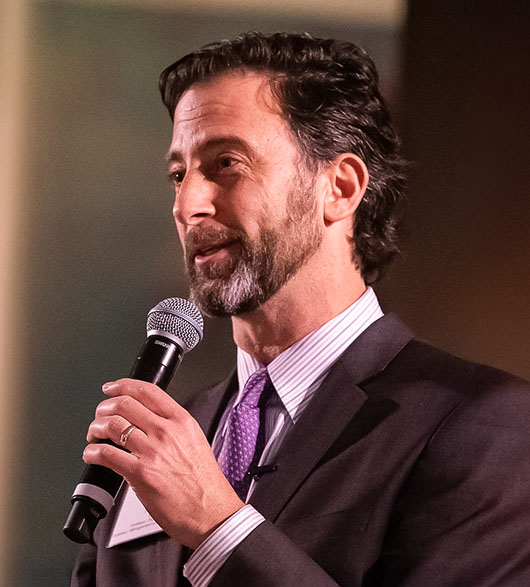

Faculty Spotlight: Eli Finkel

IPR social psychologist’s research sits at the intersection of relationships and politics

Get all our news

With this sort of confusion that I had when I was looking at politics, I started to realize that we have created—Democrats and Republicans, for example—the most toxic marriage I can fathom.”

Eli Finkel

IPR social psychologist

From a young age, IPR social psychologist Eli Finkel pursued a “life of the mind,” driven by curiosity. While studying social psychology as a Northwestern undergraduate, he quickly discovered his primary interest: relationships.

“Why is an individual attracted to one partner but not another? Why do some relationships end in divorce and others end up happily ever after?” Finkel said. “Those sorts of questions were extremely interesting to me, just like I think they’re interesting to most people.”

Until 2018, Finkel’s research primarily focused on romantic relationships, including initial attraction, marital dynamics, and the pursuit of shared goals. His book, the highly lauded The All-or-Nothing Marriage: How the Best Marriages Work (2017), delved into his research on the institution of marriage over time, finding that the best marriages of today are better than the best ones of the past.

The same curiosity that led him to study relationships also guided him to a seemingly unrelated field: politics.

American Partisans: ‘The Most Toxic Marriage I Can Fathom’

Finkel, like many, was always politically aware, but considered it a hobby. That all changed with Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings to become a Supreme Court justice in July 2018. He watched, transfixed and disturbed, at the Rashomon-like scene as Kavanaugh and Christine Blasey Ford provided irreconcilable testimony before Congress regarding her accusation that he had sexually assaulted her in high school.

Among the alarming conclusions Finkel drew from this event is that the addition of so much new information barely changed anyone’s mind. Gallup polling conducted before and after the hearing showed the share of people with an opinion on the matter grew, but the gap in percentages of those for and against Kavanaugh’s confirmation remained virtually unchanged—and Democrats and Republicans remained highly polarized in their views.

Finkel felt that America was split between two realities. “I started to think, ‘I don't know if there's a future for my nation,’” he said. “‘I think we're driving off a cliff and I don't know where the off-ramps are.’”

The concern he felt following the hearing served as a catalyst for Finkel. He saw all-too-familiar patterns: The deep divide between Democrats and Republicans looked to him like a dysfunctional marriage—filled with contempt, negative interpretations, and isolation from opposing views. It pushed Finkel to take his experience in relationship science and apply it to politics.

"With this sort of confusion that I had when I was looking at politics, I started to realize that we have created—Democrats and Republicans, for example—the most toxic marriage I can fathom,” he said.

In Science, Finkel and his co-authors, including IPR political scientist Mary McGrath, review evidence that the level of hatred partisan Americans feel toward their political opponents far exceeds their level of disagreement on policy. “This is the sort of thing that you see in corrosive marriages,” he said. “The sort of fights that, from an external perspective, you might say, ‘I don't really see why that was such a big deal,’ become sources of absolute, extreme moral outrage.”

Such misperceptions apply well beyond the domain of policy. Finkel’s research shows that Americans have convinced themselves that those in the other major party hold values that oppose their own, whereas the opposite is true. Americans are “fighting phantoms,” as Finkel puts it. “They have created demons in their heads and are doing battle against those demons rather than engaging in partisan competition against the people who actually exist,” Finkel said.

Such misconceptions, Finkel said, are fueled by the news media and social media. In a study with Northwestern postdoctoral scholar in psychology Michalis Mamakos (PhD, 2023), he found that comments by politically engaged Reddit users are toxic even if they are not discussing politics. “This suggests that the most toxic people are especially likely to opt in to political discourse,” Finkel explained, which makes the public sphere unwelcoming for the rest of us.

Free Speech on Campus: Finding the Right Fault Line

Finkel criticizes the prevailing either/or debate on free speech, especially on campuses, in which the question becomes, do you prioritize the First Amendment—or do you protect individuals from harmful speech?

"I think that’s the wrong fault line," Finkel said. “It ignores the people who are on the periphery who might enter the public sphere, who might enter the debate, but are prevented from doing so because the most aggressive voices turn the public sphere into the Thunderdome."

Instead, Finkel sees a need for an expansive approach to talking about important ideas, even potentially hurtful ones, while rejecting harmful ways of communicating such ideas.

"We shouldn't get to communicate in a way that prevents other people from joining us," he stated.

In February, Northwestern President Michael Schill appointed Finkel to a committee of 11 distinguished senior faculty members tasked with examining the issues of free expression and institutional speech. Finkel underscores the importance of respectful, open dialogue and thoughtful discussion to bridge divides. "I really do value the classic idea that we resolve things through debate and discussion," he said.

That same belief led him to launch the Center for Enlightened Disagreement at the Kellogg School of Management with his colleague Nour Kteily, professor of management and organizations and co-director of Kellogg’s Dispute Resolution Research Center.

“We’re not shying away from disagreement. Nobody wants a one-party state. Let's find where the actual disagreement is and lean into it,” he said. “I don't want to have people so polite, that they just pretend to get along with everybody and probably just reinforce whatever the status quo is. I want to have serious, intense, robust disagreement.”

The center is built on research, outreach, and curriculum development and will serve as a hub for discussion. It aims to harness the positive aspects of disagreement while reducing its negative aspects, such as false disagreements and unwillingness to listen. The goal is to identify and address conflicts openly and constructively, rather than letting them become corrosive.

“We want to be a place where people from all walks of life can take disagreement and make goodness out of it rather than toxicity,” he said.

Eli Finkel is professor of psychology and management and organizations and a Morton O. Schapiro IPR fellow.

Published: August 15, 2024.