How Has COVID-19 Affected Children and Adolescents?

IPR experts discuss how the pandemic altered childcare, schooling, and mental health

Get all our news

One of the things we did is we kept everybody home, and we also kept kids out of school. I think it's worth going back and thinking now—did we make the right trade off?”

Jonathan Guryan

IPR economist

IPR experts Emma Adam, Terri Sabol, and Jonathan Guryan spoke on a panel about the impact of the COVID-19 panel on children and adolescents moderated by Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach (seated from left to right).

On March 11, it will be three years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. In that time, the world’s youth have experienced lockdowns and upheavals in their school, work, and social activities. Headlines have increasingly warned about substantial learning losses and critical mental health crises.

Four IPR experts discussed what research indicates about the effects of COVID-era events and policies on February 6, tracing how U.S. children and adolescents have fared in the short term and what we might expect in the long term.

“I am so proud of the work that IPR faculty and frankly, the academy, did during this time period, but of course, our work is not over,” IPR Director and economist Diane Schanzenbach said in introducing the panelists. “We see lingering impacts of COVID-19—with, for example, some estimates suggesting that about half a year of learning was lost for children.”

5-Year-Olds and Under: Responsive Policy Kept Childcare Open

“If you remember, way back in 2020, there was this really grave concern that the childcare system was going to completely collapse,” IPR developmental psychologist Terri Sabol explained. She referred to the mandatory closures of childcare programs in an industry already operating on slim margins.

But Sabol noted that the federal government’s policies around childcare were “actually pretty good” as the CARES Act, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, and the American Rescue Plan, both signed into law by President Joe Biden in 2021, pumped funds into childcare programs.

Sabol’s own research with several Northwestern graduate and undergraduate students shows that in Illinois, these funds were equally distributed across neighborhoods, for the most part. One exception was that urban areas were more likely than rural ones to receive funding, likely due to better communication about the program amongst childcare staff and centers in cities, she speculated.

IPR economist Kirabo Jackson asks a question during

the Q&A portion of the panel.

Though the pandemic brought a push to invest in childcare, she noted momentum has dwindled since then. Recent spending bills have allocated little toward childcare policies.

“With this context, we still have major challenges within the early childhood system,” Sabol said, pointing to 19 billion hours in missed learning opportunities and childcare workers’ persistently low pay of around $12 per hour on average, and many childcare workers leaving the field.

Along with these challenges, a national decline in enrollment in early childhood education and in public kindergarten programs has occurred. Locally, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) lost more than 2,700 kindergartners from 2019 to 2022.

While preschool enrollment did drop during the pandemic, it is beginning to rebound, Sabol said. The jump provides an opportunity to examine if universal pre-K—which CPS rolled out in 2019 before the pandemic hit—brings kids back to early childhood education programs. To find out, she and Schanzenbach are collaborating to analyze enrollment data from Chicago’s free, full-day, universal pre-K program.

“The bright spot here is that local and state policy actually has been responsive to the needs of young children and families,” Sabol said about Illinois’ and Chicago’s recent childcare policies.

6- to 18-Year-Olds: Lopsided Learning Losses, More Than a Funding Issue

“The headline is, ‘Kids Learned Less During COVID,’” IPR economist Jonathan Guryan said, with some falling behind more than others.

He cited research by Stanford’s Sean Reardon and Harvard’s Thomas Kane calculating that based on test scores, students in third through eighth grades lost the equivalent of half a year of learning in math and a quarter of a year of learning in reading.

“Those lost-learning opportunities were not evenly distributed,” Guryan said. “School districts with more Black and Hispanic kids had larger losses, and districts with higher poverty rates also had larger losses.”

He singled out another pattern that emerged during the pandemic: Higher rates of remote instruction were linked to larger learning losses, and this was especially true of higher poverty schools, where students spent more time learning remotely.

“We saw this not just around the country, but at home here in Chicago,” Guryan explained, pointing to dramatic declines in students’ National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test scores from 2019 to 2022.

In May 2020 when CPS was in remote learning, roughly 80–85% of fifth-to-twelfth-grade CPS students logged in to Google Meet or Google Classroom, the tools CPS used for online learning. And 25–30% did not connect at all—and the percentage was even lower for the very youngest students: Only about a third of kindergartners and about half of first and second graders logged in.

Guryan said that policymakers had some very hard decisions to make about what to do keep people safe and reduce the disease’s spread.

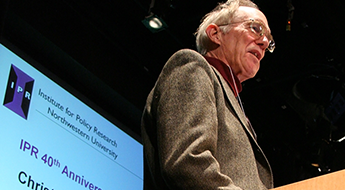

Jonathan Guryan shares about the large learning losses

students in K-12 experienced during the pandemic.

“One of the things we did is we kept everybody home, and we also kept kids out of school,” he said, noting how these decisions became politicized. “I think it’s worth going back and thinking now—did we make the right trade off?”

In response to the learning losses and re-opening schools, the federal government’s policy was to open its coffers and invest an additional $190 billion into schools across 2020 and 2021, or about one-quarter of what schools normally spend in a year, with much of that going to higher poverty districts.

But Guryan argued to address the learning losses, issues exist beyond providing more funding. While education spending is necessary, policymakers should think beyond solving them with just more funding.

“The money has to be spent in an effective way—in a way that actually helps kids—and that in itself is a challenge,” he said.

12- to 29-Year-Olds: Increased Depression and Anxiety, Fragile Finances

Declines in mental health during the pandemic have been tracked and discussed frequently. But IPR developmental psychobiologist Emma Adam emphasized that “adolescents were not doing well before the pandemic.”

Starting in 2012, the rates of depression among 12- to 17-year-olds had begun to increase dramatically, according to some studies, including her own.

Adam explained that one issue when comparing levels of depression before and after the pandemic is that prior to the pandemic, survey data were often collected from at-home interviews by trained surveyors and are more reliable than the mixed-survey format used during the pandemic. Still, she underscores that both types of data hold meaning.

IPR developmental psychologist Emma Adam answers

a question during the Q&A portion of the panel.

Multiple studies comparing levels of depression before and during the pandemic show a slight increase in already high depression rates, but not dramatic ones, she said. For anxiety, however, results are mixed. Some studies show declines and others, increases or no changes. Adam’s own data collected before and during the pandemic finds declines in school and peer sources of stress and anxiety, but increases in home and health-related stress.

“Especially during the early pandemic, there was some relief of social anxiety among students when they didn’t have to go to school, and they were under lockdown,” Adam said. “The change in condition might [have been] bad for learning, but perhaps not as adverse for emotional outcomes as we would have expected.”

For young adults, however, the data paint a different picture: 33% of those between 18 and 29 years old reported clinically significant levels of depression, and 40% reported clinically significant levels of anxiety according to large-scale data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau between April 2020, around the pandemic’s start, and August 2022. Levels were higher still for women in this younger age group. Those in middle and older adulthood reported less anxiety and depression across the pandemic, with lower rates found for each decade older of age.

Even though these data were pulled from a few survey questions and not clinical interviews, Adam called the levels for young adults “concerningly high,” saying they can be partially explained by the economic conditions of younger adults.

“What we find is that the factors that differ between younger and older adults that matter for this age disparity [in depression and anxiety] are related to economic precarity,” Adam said.

In fact, an analysis by Adam and Sarah Collier Villaume (PhD 2022), a former IPR graduate research assistant, shows that greater economic instability explains at least one-third of the gap for depression and anxiety between the older and younger Americans, the latter of whom earn less and are less likely to own their homes.

Adam added that older adults experienced less depression after receiving the vaccine, but they have not seen any signs of recovery for 18- to 29-year-olds.

She believes, based on her data, that rather than health concerns, it is the social and economic stress and uncertainly associated with the pandemic and repeated exposure to news on troubling national and world events, that is contributing to sustained high rates of depression and anxiety among youth.

Emma Adam is the Edwina S. Tarry Professor of Human Development and Social Policy. Jonathan Guryan is the Lawyer Taylor Professor of Education and Social Policy. Terri Sabol is associate professor of human development and social policy. Diane Schanzenbach is the Margaret Walker Alexander Professor of Human Development and Social Policy and IPR director. All are IPR fellows.

Published: February 27, 2023.