The Science and Practice of Street Outreach in Illinois

Symposium examines lessons learned and the future of a promising violence reduction strategy

Get all our news

We know, without a doubt, with 100% certainty, that outreach can reach those in harm’s way successfully without relying on the criminal justice system.”

Andrew Papachristos

IPR sociologist and co-director of N3

N3 executive director Soledad McGrath moderates the final panel on the future of street outreach during N3's 2021 Symposium on Dec. 8, 2021.

At the end of November, Chicago’s homicide record for the year tallied 739, which was the highest number for any city in the United States and a 3% increase over 2020.

With such alarmingly high numbers, people are searching for viable strategies to address the violence. A December 8 symposium held at Northwestern University examined a central violence prevention strategy in Chicago—street outreach. It was hosted by the Northwestern Neighborhood & Network Initiative (N3), which is housed within the Institute for Policy Research (IPR).

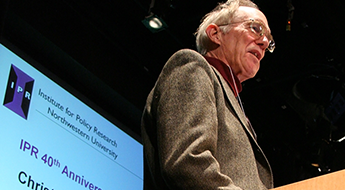

Andrew Papachristos shares remarks during the opening

of the N3 symposium.

“We know, without a doubt, with 100% certainty, that outreach can reach those in harm’s way successfully without relying on the criminal justice system,” said IPR sociologist Andrew Papachristos, who co-directs N3 with IPR research professor Soledad McGrath, both of whom co-organized the symposium.

The symposium, “Advancing the Science and Practice of Street Outreach: Lessons Learned and the Future of Street Outreach in Illinois,” brought researchers, nonprofit leaders, and street outreach professionals together to discuss emerging research on street outreach and how to continue building the infrastructure to strengthen the field. Chris Patterson, Illinois’ newly named assistant secretary for violence prevention at the Illinois Department of Human Services, delivered opening remarks. More than 300 people attended the event, either in person or online.

Many speakers underscored why street outreach workers and organizations are essential to reducing gun violence. Outreach professionals use and strengthen relationships throughout their respective communities to connect with people at the highest risk of being victims of gun violence.

In addition to preventing violence, street outreach organizations provide valuable social services to communities.

Chris Patterson gives opening remarks.

“They’re also anchoring institutions for neighborhood safety, wellbeing, dealing with the issues related to housing, mental health, education, and justice,” Patterson said.

Additionally, many panelists noted that street outreach workers need more professional and personal support to do this critical work. N3 also presented new survey findings that give insights into outreach workers’ on-the-job challenges.

The Violence Intervention Worker Study, or VieWS, was developed in partnership with leaders in the Chicago outreach community and Professor David Hureau, the University at Albany. The survey finds finds that outreach workers have high levels of exposure to violence while on the job. About 77% of workers report seeing someone attacked while on the job, and 57% have seen someone shot at but not wounded.

Outside of work, 43% find it difficult to pay their monthly bills, and more than half of outreach workers say they are underpaid.

Despite these barriers, the panelists identified and called for additional services and policies to help outreach workers and organizations foster safe neighborhoods and communities.

“A healthy public safety system requires equitable policies, robust investment in communities and wraparound services, and community-center governing structures,” said Rev. Ciera Bates-Chamberlain, executive director of Live Free Illinois, in her closing remarks.

She emphasized that gun violence needs to be treated with more urgency to save more lives.

“People have the right to live in safe and healthy communities,” she said.

Violence Intervention Workers Survey | Assessing Risk | Building the Evidence Base | The Future of Outreach

Panel 1: The Violence Intervention Workers Survey: An In-Depth View of Outreach Workers in Chicago

The VIeWS survey highlighted critical concerns about street outreach workers’ wellbeing and the challenges they face to do their jobs.

Even those on the panel leading the work were shocked at the high levels of violence exposure and trauma for the workers the study revealed, but they were glad to confront them.

“[I]f we don't talk about the exposure, then I think we're doing more harm to our staff and the people in the field,” panelist Jorge Matos, Director of Safe Streets, Alliance of Local Service Organizations (ALSO), said.

The first panel discusses findings from the VIeWS project

and on-the-job challenges for street outreach workers.

Patterson, who took part in the panel discussion, pointed to the challenge of asking people already traumatized by violence to put themselves back into the violence of the streets.

“It’s like almost a cruel game or cruel joke we're asking people to do, who have fought their whole life to try to get out of a situation, and then we ask [them] to go back into the situation,” he noted.

The survey findings also pointed to the need for mental healthcare for workers.

Cuitláhuac Heredia, Restorative Justice Street Outreach Coordinator, New Life Centers, said, “You’re retraumatized on a weekly basis, and it just feels like the burden can be very stressful if you don’t have ways to cope, you don’t have ways to vent, to speak, to build healthy relationships within your own life, how can you do that [work] on the streets?”

Papachristos, the panel moderator, stated that despite the violence, trauma, and low pay, street outreach workers are doing remarkable work to stem violence in Chicago, and were especially effective in easing tensions between the Black and Latino communities after George Floyd’s murder in May 2020.

“It's a profession that's emerging and being carried on the backs of 200 individuals. We have phenomenal relationships and community. What does 400 outreach workers get us?” Patterson asked.

Panel 2: Assessing Risk: Frontline Perspectives of Navigating the Dynamics of Gun Violence

Risk assessment is one tool outreach professionals use to evaluate an individual’s chances of involvement in violence, but it can be challenging to measure. Angelica D’Souza, a research project manager at N3, pointed out that individuals often move between low and high risk depending on conflicts in the neighborhood.

The second panel engages senior outreach professionals

about the dynamics of gun violence risk.

Since risk levels constantly change, building relationships is essential for outreach workers. Having these connections helps give them a “license to operate,” or LTO, in neighborhoods.

“What [LTO] means is that your credibility is good, that when you go into that community, your character speaks for itself,” said Damien Morris, senior director of violence prevention at Breakthrough. “Therefore, your chances of doing the work or bringing individuals to the table is that much better.”

Demetrius Bunch, CP4P lead coach supervisor at Claretian Associates, noted that outreach workers need to continually show up in the communities they serve and be sincere about reducing violence. He recalled how one participant laughed at him when he first showed up in his outreach uniform about five years ago. Now, that participant is one of Bunch’s best outreach professionals.

“You can’t give up. Consistency is key,” Bunch said.

Additionally, the panelists discussed how to measure success and professionalize the field, as well as the qualities of a good outreach worker.

Morris and Bunch also acknowledged women outreach workers’ contributions to the field. Morris said, “We’ve seen participants that have a history of being the troublemaker, but when it comes down to it, who they respect is the women.”

Panel 3: ‘Building the Evidence Base’

How can research help practitioners, and what can researchers learn from practitioners? How can both work to create more meaningful partnerships?

Led by N3’s Dallas Wright, the panelists on “Building the Evidence Base” discussed the challenges and opportunities these partners face in conducting, creating, and consuming “engaged research.”

Research benefits practitioners because it strengthens their work and asks critical questions, remarked Vaughn Bryant, who directs Metropolitan Peace Initiatives. “So, over time, you can see trends and how people operate and how certain sorts of interventions can create change.”

The third panel shares their thoughts on how researchers

and practitioners can integrate their work.

To create more understanding between the very different practitioner and research cultures, the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Kathryn Bocanegra pointed to the need for researchers from backgrounds like hers, a practitioner who became a researcher, as well as researchers who become practitioners.

Also critically important for each side is the idea of building trust and opening up to others, Bryant said, calling it a “two-way street.”

“It's hard to go deep with somebody when you don't do it for yourself,” he said.

Bocanegra also discussed the importance of community accountability and feedback.

“I believe having research collaborations with people who are embedded within communities and who are accountable to communities will have practice insights,” she said.

Joseph Guisti of the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago spoke about his desire to see a more diverse set of researchers “swell the ranks.”

“It feels like we're really at us at a special point right now as we're thinking about developing a profession,” Guisti said. “I want to see our outreach workers get PhDs in sociology. It's not impossible."

Panel 4: Where Do We Go From Here? The Future of Outreach in Illinois

According to the panelists, one way to expand the field is to invest in outreach workers who are currently doing the work. While investments usually cost money, Vanessa Perry DeReef, director of training at Metropolitan Peace Academy, proposed a solution that helps build the “power of the human resource.”

The fourth panel talks about future directions and policies

for street outreach in Chicago and Illinois.

“We get to know the people who are doing the work, and so we build community,” she said and stressed that trust and transparency are critical tools to outreach work.

McGrath, who moderated the discussion, also asked panelists how leaders can ensure more equity across their organizations. Eddie Bocanegra, senior director of READI Chicago at Heartland Alliance, who served 14 years in prison and spent four years doing outreach work, pointed out that outreach work is stagnant, and many workers do not have the opportunity to develop marketable job skills.

“I think to myself that’s not equity,” he said. “Equity is creating an opportunity where people come in, and you invest in that person.”

Teny Gross, executive director of Institute for Nonviolence Chicago, added that “We’re not going to get better unless we have a culture that is critical,” and explained that sometimes leaders need to take a step back and listen to different perspectives.

At the end of the panel, the speakers agreed that research and changes are needed to reduce gun violence further. Bocanegra said, “In Chicago, we have this wonderful opportunity. We’re evaluating many of our initiatives here, and there are a lot of lessons learned that we just cannot sit on. We need to further develop that and scale that."

Find out more about the Northwestern Neighborhood & Network Initiative (N3) and watch the symposium videos.

Photo Credit: Rob Hart

Published: December 14, 2021.