The History of Diversity as an Educational Value

Study examines the origins of affirmative action in higher education

Get all our news

The diversity rationale is not really a creature of the ’70s. It’s actually a creature of the early 1960s, which is a very different moment in American political life.”

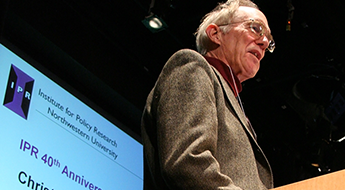

Anthony Chen

IPR Sociologist

Boston protestors offer their support for the lawsuit by Students for Fair Admissions

against Harvard University in October 2018.

In November, an appellate court ruled on the latest challenge to the use of race in college admissions, agreeing with the lower court that there wasn’t enough evidence to show that Harvard intentionally discriminated against Asian American students. With the Supreme Court likely to hear an appeal, new research sheds new light on the origins of affirmative action and underscores how its being overturned could drastically set back diversity on college campuses.

This idea that diversity is educationally valuable—or the “diversity rationale”—is often seen as coming out of the seminal 1978 Regents of California v. Bakke Supreme Court case. But IPR sociologist Anthony S. Chen and co-author Lisa Stulberg of New York University find it started much earlier.

In Bakke, the court struck down racial quotas in the admissions process, but held that race could still be used to foster racial diversity.

“The diversity rationale is not really a creature of the ’70s,” Chen explained. Examining historical records dating back to the 1960s, he and Stulberg discover something else entirely: “It’s actually a creature of the early 1960s, which is a very different moment in American political life.”

The two researchers focus on little known but critically important conversations in the early 1960s, when admissions officers and administrators at top universities saw that American society was changing. They decided that their institutions should take the lead in enrolling students who differed from the White, Anglo-Saxon Protestants who had long made up their student bodies.

Those like Wilbur Bender, Harvard’s dean of admissions during the Eisenhower era, believed that classes of diverse students improved education. He set out to disseminate his ideas in 1961, just after the country had elected its first Roman Catholic president—John F. Kennedy.

“In the early 1960s, the country was beginning to engage more sympathetically with human difference in a way that it had not done in prior years,” Chen said.

At Harvard and Columbia, for example, college officials sought to admit diverse students, including Black students, even before the civil rights movement transformed the national agenda. “When [the idea of diversity] entered into circulation in those institutions, it meant religion, ethnicity, geography, gender, race, class, all those different things,” Chen noted.

But a shift unfolded in the 1960s. “In 1963, race became elevated in salience because of the civil rights movement,” Chen said.

College officials continued to value many different aspects of an applicant’s background, but racial diversity was top on their minds.

Chen and Stulberg’s findings challenge the idea that the diversity rationale was hurriedly concocted in the 1970s to justify racial preferences that could not otherwise survive legal and constitutional scrutiny. Their findings call into question the intense skepticism that is often brought to bear on the underlying motives of schools that wish to compose a diverse class for its educational value.

Even as researchers like Chen and Stulberg continue to share their new findings, they see a strong chance that the Supreme Court will take up the Harvard case at a time when the stakes for diversity and affirmative action could not be higher.

If the Supreme Court “gets rid of affirmative action, it would turn the clock back,” Chen said. “But it wouldn’t just roll us back to 1978, which is the year of the famous Bakke case. It would roll us back before 1961.”

Source: Chen, A., and L. Stulberg. 2020. Before Bakke: The Hidden History of the Diversity Rationale. University of Chicago Law Review Online.

Anthony Chen is associate professor of sociology and of political science (by courtesy) and an IPR fellow.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons, Whoisjohngalt

Published: December 16, 2020.