IPR@50: The First Decade (1968–1978)

Innovation and Continuity

Get all our news

Protests and riots broke out across the nation in spring 1968 following Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination.

This is the first of a five-part series that will examine how IPR has grown and evolved in each decade. IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach offers a preview of the June 6-7 anniversary conference here.

[View a timeline of IPR's First Decade]

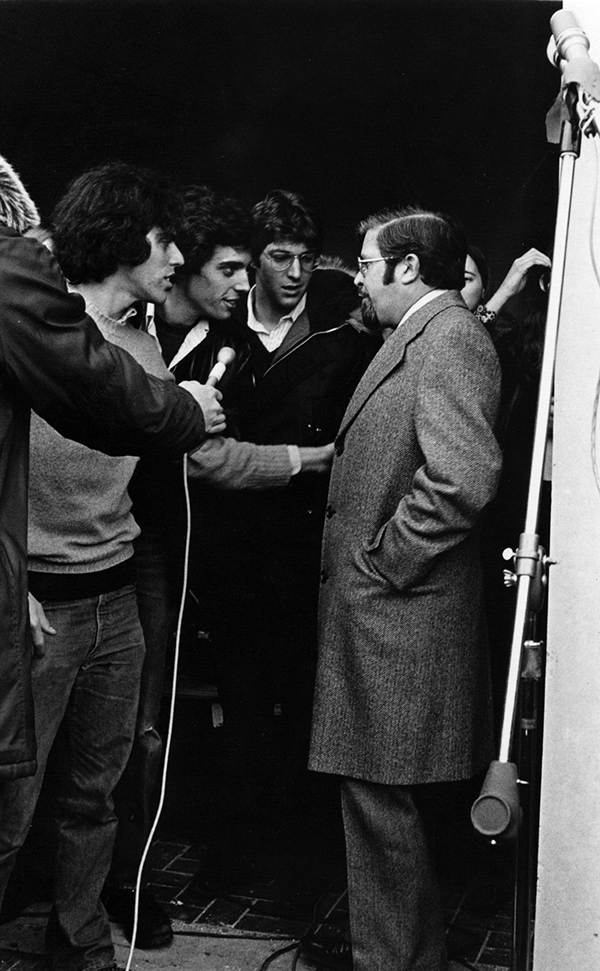

“Stop the Cities Burning!”

The Center for Urban Affairs—now IPR—was born in 1968, a time of urban violence, turmoil, and fear. Concerned faculty and observers thought universities across the country needed to be more involved in the cities they called home.

Northwestern University faculty, seeing the explosion of racial, social, and political unrest in Chicago—such as the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and police violence during the Democratic National Convention, as well as protests on their own campus—committed to use their research and teaching to engage in improving the city.

in the IPR conference room.

An initial grant of $700,000 over three years, 1969–1971, came from the Ford Foundation to create a center devoted to urban studies and policy change.

As John McKnight, communications professor and former associate director of the Center, recalled, the grant’s purpose was “to get universities to do basically useful, applied research to stop the cities burning!”

The Ford Foundation distributed grants to nine university centers, including at Northwestern, to develop urban affairs research, training, internship, and social service programs.

The Center got started as the Ford Foundation “was trying to figure out a way that the universities could begin to solve some of these urban neighborhood problems,” Dan A. Lewis, an early Center researcher, social policy professor, and IPR associate, remembered.

A small group of interested faculty from multiple disciplines had been voluntarily meeting and working together since the late 1950s as the Center for Metropolitan Studies, and they formed the core of the new Center. One of their number, Raymond Mack, a sociologist well-known for his work on race, was tapped to be the first director.

From the very beginning, the Center was notable for being interdisciplinary and for its commitment to what was known then as “action research programs,” research in cities that partnered with residents and community groups and aimed at finding solutions for complex urban problems of poverty, race, and inequality while also contributing to science and theory.

Fifty years later, these two fundamentals of IPR remain, not just as a proud legacy, but as part of the Institute’s DNA—making IPR what it is today.

Ensuring the Future

Raymond Mack.

Northwestern University provided a welcoming atmosphere for the new Center.

Early faculty member John Heinz, a legal scholar and social scientist, recalled how “interdisciplinary research was already in existence” at the University. Examples included the Council for Intersocietal Studies and the group he headed, the Program in Law and the Social Sciences.

Under Mack’s far-sighted guidance, the new Center employed its funding to guarantee its future.

One of Mack’s great innovations was to create half-time faculty appointments at the Center. The various departments—sociology, political science, and communications, for example—supplied the other half. Mack was able to recruit 24 half-time faculty members rather than 12 full-time ones the grant initially contemplated. With continued commitment and funding for these faculty from Northwestern, the Center long outlived most other university urban affairs programs while maintaining its interdisciplinary character.

By the end of the Center’s first decade, in 1978, there were nearly 50 faculty from 15 schools and departments. The breadth of disciplines included not just the social sciences such as sociology, political science, economics, psychology, anthropology, and geography, but also history and art history; journalism and communications; education and ethics; management, industrial relations, and law; engineering and transportation; and health administration and epidemiology.

“Relevant and Utilized” Policy Research

In many ways, the Center operated in its first decade in similar fashion to IPR today. The Center was organized into research project groups and held study groups and seminars to explore ideas and issues.

At the same time, researchers went out into the city to discover the basic determinants of urban problems. What factors lead people to feel and be secure? What are the causes of better health and longer life? What elements go into educating in schools and beyond? Faculty and their students worked to create policy change through what were known as “action programs.”

They connected to communities directly through methods similar to those used in community organizing—often beginning with painstaking grassroots meetings in the neighborhoods—and built partnerships with neighborhood organizations, local governments, and private agencies. Such work “increases the probability that our policy research will be relevant and utilized,” wrote Louis Masotti, the Center’s second director, in the 1978 Center report on its first decade.

Today’s partnership with the Evanston public schools, with funding from the Lewis-Sebring Family Foundation, is the latest example of IPR’s continuing commitment to working with local institutions to better their serve their community.

The Center’s accomplishments in the first decade focused on what Lewis called “strengthening urban communities” by investigating key urban problems such as affordable housing and segregation, reactions to crime; police conduct; child welfare; and transportation. Some noteworthy projects included:

- Uncovering and publicizing redlining practices in Chicago—carried out by John McKnight, and fellow Center researchers Andrew Gordon, Leonard Rubinowitz, and Marcus Alexis—that paved the way for passage of the Community Reinvestment and Home Mortgage Disclosure acts.

- Studying reactions to crime, a five-year research project, which examined victims and their behavioral and psychological responses to crime. Long-time IPR faculty Wesley G. Skogan and Dan Lewis did some of their earliest work on these projects. Lewis noted that with this project, “we in many ways invented community crime prevention.”

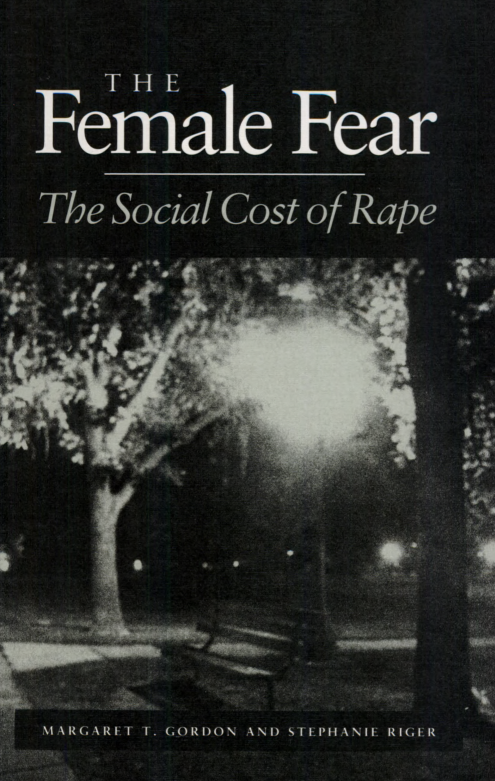

- Analysis of women’s attitudes toward rape and their adaptive behaviors, eventually resulting in Center researchers Margaret Gordon (the Center’s third director) and Stephanie Riger’s groundbreaking 1991 book, The Female Fear: The Social Cost of Rape.

- Evaluations of the successes and failures of bureaucracies and services, such as the Community Renewal Society in Chicago’s Kenwood-Oakland neighborhood, under the direction of Raymond Mack, Andrew Gordon, and others.

- An experimental study of access to government information in Chicago and Illinois, undertaken by Andrew Gordon and John Heinz.

Gordon and Stephanie Riger

Arising out of its “action research,” the Center also played a role in initiating and developing viable community groups and organizations. The Law Enforcement Study Group (LESG) is a notable example. Formed in 1970 when 11 Chicago-based community organizations asked the Center to guide interdisciplinary research, the LESG became an important voice in criminal justice reform in Cook County for 15 years.

During its first five years, LESG was part of the Center, where researchers produced a series of reports about criminal justice practices. The partner organizations used the reports to press for reforms with some success: LESG reports played roles in the decision by the U.S. Department of Justice to file a federal lawsuit to eliminate racial employment discrimination in the Chicago police; in the Evanston police establishing a summons (or “ticket”) program for minor ordinance violators instead of requiring them to post bond or spend time in jail if unable to make bond; and in the replacement of the office of Cook County coroner with a medical examiner. In 1975, LESG became an independent nonprofit organization.

Throughout its first decade, the Center focused on the twin goals of careful research into the basic determinants of urban problems and active engagement in policy change through interdisciplinary cooperation. These goals continue in IPR’s mission to support excellent social science research and promote its impact on policy, now marking 50 years in action.

“The Center has done very well in surviving and prospering and being quite consistent with the original mission, I think,” Heinz said. “It still has very much the same kind of vision of action research, committed research, research that has a policy focus and is directed toward social amelioration.”

John Heinz is Owen L. Coon Professor Emeritus of Law. He joined the faculty of the Center for Urban Affairs in 1972 and is an IPR faculty emeritus. Dan Lewis is professor of human development and social policy, director of the Center for Civic Engagement, and an IPR associate. He joined the Center for Urban Affairs in 1975. John McKnight is the founder and co-director of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute. He joined the faculty of the Center for Urban Affairs in 1969 and is an IPR faculty emeritus.

Read more about the IPR@50 Conference here.

Article by Evelyn Asch, IPR Research Associate. Photo credits: Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress (top), IPR/NU Archives (John McKnight and Raymond Mack).

Published: March 20, 2019.