Global Migration: ‘The World’s Greatest Anti-Poverty Program’

New York Times reporter recounts one family’s journey from Manila’s slums to Galveston’s suburbs

Get all our news

I came to think of the Villanuevas as a kind of retort. With a house in the suburbs and kids on the honor roll, they achieved in three years a degree of assimilation that used to take three generations.”

Jason DeParle

New York Times Reporter

In 2018, remittances to low- and middle- income countries reached a record high. Migrant workers sent back an estimated $529 billion to countries such as India, China, Mexico, and the Philippines.

“Migration is to the Philippines as what cars once were to Detroit. It’s the civil religion,” said Jason DeParle, a New York Times senior reporter, at his February 26 lecture at Northwestern University in Evanston.

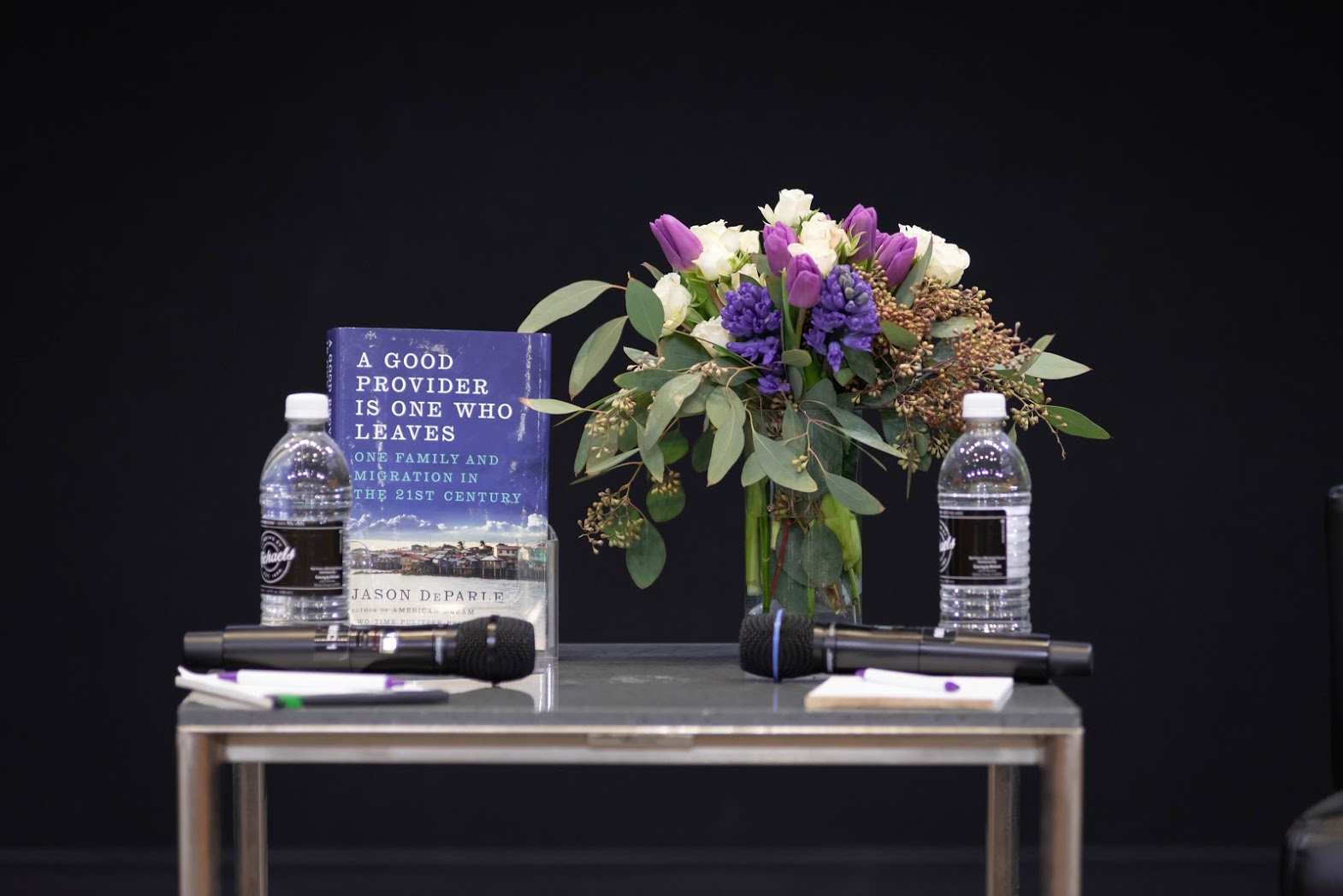

No country does more to promote migration than the Philippines, DeParle told the audience. In recounting the narrative arc of his latest book, A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves, he detailed how global migration allowed one family living in Manila’s slums to leave poverty.

The Institute for Policy Research (IPR) co-sponsored the event with the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

“By incorporating social science research into his narrative, Jason offers a compelling, on-the-ground view of a person or family or a whole generation, all the while weaving it into the larger social and policy fabric of the times,” said IPR and Medill mass communication scholar Rachel Davis Mersey in introducing him.

Following his lecture, DeParle further explored implications of global migration with IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach.

The One Who Leaves

As a young reporter in 1987, DeParle moved into the home of Tita and Emet Comodas and their five children while on a fellowship in the Philippines studying poverty. The Comodas family lived in Leveriza, a Manila shantytown—a development of scrap-wood shacks where some of the city’s poorest resided.

To support his family, Emet, like many Filipinos, took a job in Saudi Arabia, where he earned 10 times more cleaning pools than he did in Manila. The job provided money for new school uniforms, medical care for a sick daughter, and indoor plumbing. His remittances would also eventually pay for his and Tita’s middle child, Rosalie, to go to nursing school—the surest way for a Filipino woman to advance.

“If you were going to pick a kid in the slums with the drive to get out, you wouldn’t have picked Rosalie,” DeParle explained.

Rosalie was shy, with average grades. But her attendance in school was perfect, an accomplishment that took grit during a period of war and revolution in the Philippines.

After passing her nursing test in the Philippines, she ended up as a migrant worker in Saudi Arabia like her father. As a migrant worker, Rosalie’s salary gave her the financial freedom to send money to her family, shop, and open a credit card.

In the Middle East, she met and married Chris Villanueva, also a Filipino migrant worker. They had three children—Kristine, Lara, and Dominique—who spent some of their early years living apart from their parents in the Philippines with Rosalie’s family.

As DeParle began writing about Rosalie for the New York Times Magazine in 2007, he realized her story was a global story.

“The lightbulb moment for me in understanding the importance of global migration was learning that remittances—the sums that migrants send home—are three times the world’s foreign aid budgets combined,” DeParle said.

A House in the Suburbs

After 20 years of waiting to realize her dream of working in the U.S., Rosalie finally got her visa in 2012 and started a nursing job in Galveston, Texas, an hour outside of Houston. Chris and the children joined her six months later.

DeParle also started his book around this time. He chronicles the family’s struggle to adjust to living together after years of separation, how work became a way for Rosalie to assimilate, Chris’ difficulty finding a job, and the children’s setbacks and triumphs in school.

“She came expecting Disney World, and she wound up in a declining blue-collar town with a vista of vacant lots,” DeParle said.

Three years after arriving, Rosalie purchased a home on a cul-de-sac in a Houston suburb called Texas City, and her family had adjusted to U.S. life. A month later, Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign. DeParle pointed to the candidate’s fiery labels of immigrants as “terrorists,” “criminals,” and “welfare cheats.”

“I came to think of the Villanuevas as a kind of retort,” DeParle said. “With a house in the suburbs and kids on the honor roll, they achieved in three years a degree of assimilation that used to take three generations.”

The Feminization of Migration

Following the lecture, DeParle and Schanzenbach discussed how increasing numbers of female migrants has affected gender relations.

“What happens in the three-generation arc of the story is that migration feminizes—in part because the work feminizes,” DeParle explained. Rosalie earned three times her husband’s salary and that financial imbalance could cause tension, he said.

Despite these tensions, Rosalie and Chris established a new life in America, recently becoming U.S. citizens. They are currently saving for another round of naturalization fees, so their children can also gain citizenship.

Migration became Rosalie’s “vehicle of salvation,” DeParle said. “It’s good when your country is the place where people go to make dreams come true.”

Jason DeParle is a New York Times senior reporter covering poverty and a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist. He is the author of two books, including “A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21stCentury” (2019, Viking Press).

Photo credits: Jenna Braunstein

Published: March 19, 2020.